PROJECT

Delicatessen in history

Although the art of pork butchery in our Country seems to derive from the homonymous city of Norcia, along the entire perimeter and history of Italy cured meats and sausages are part of every Italian’s home. Even if, as we will see later, the first references to cured meats date back to Pharaoh Ramesses III, of the 20th Egyptian Dynasty (1217– 1155 BCE), it is already from the Neolithic period that the processing of the pig is intertwined with the history of man and vice versa, as shown by the detailed investigation conducted by the British paleontologist John Desmond Clark (1916 – 2002).

PROJECT

Delicatessen in history

Although the art of pork butchery in our Country seems to derive from the homonymous city of Norcia, along the entire perimeter and history of Italy cured meats and sausages are part of every Italian’s home. Even if, as we will see later, the first references to cured meats date back to Pharaoh Ramesses III, of the 20th Egyptian Dynasty (1217– 1155 BCE), it is already from the Neolithic period that the processing of the pig is intertwined with the history of man and vice versa, as shown by the detailed investigation conducted by the British paleontologist John Desmond Clark (1916 – 2002).

Specifically, it is linked to agriculture and even more to animal farming, which sees humans change their lifestyle from nomadic to sedentary.

The many findings brought to light in Vulci (8th century BCE), a rich Etruscan city situated in what is now northern Lazio and, later also in Forcello (4th century BCE), a few kilometers south east of Mantua, near the locality of Andes, solidify the belief that already in the Etruscan age animal farming was practiced in a similar manner and in accordance with the current practices. The traces discovered in these places on a sample of about forty thousand animal remains, well delineate the presence of the bodies of pigs whose limbs had been amputated during the slaughtering practice and which are supposed to have been dried and prepared for sale, as it still happens today for our prosciuttos. As for literature, we owe to Hippocrates, the father of Western medicine, the first texts about the processing of the pig and the praise of its meat. In a writing of the 4th century BCE, Marcus Porcius Cato – also known as Cato the Censor (234 – 149 BCE) – in his ‘De Agricultura’ (“On Agriculture”) equally exalts and clearly identifies the preservation of pork haunches through “perxuctus”, very dry in English, praising the taste derived from the method of drying through heavy salting. Also, in “Ab Urbe condita” (XXXV, 5, 49) by Titus Livius, known in English as Livy, the pig and its derivatives are the protagonists of a banquet entirely “ex mansueto sue factam” that is, obtained from the meek animal. Furthermore, in the ‘Satyricon’ written by Gaius Petronius, Trimalchio declares to Petronius: “As I hope to grow a bigger man, in fortune I mean, not fat, I declare my cook made it every bit out of a pig”.

As it is clear to us, pork was well present on the tables during the Roman times, where there was no lack of recipes and methods to obtain fragrant cured meats. Not only techniques for smoking and salting pork, but also a sort of ‘promotion’ of this animal, embodied in the renowned Legio X, which bore the effigy of the wild pig on the shields of the Roman army. Similarly, Pliny the Elder believed “that from no other animal is derived more material for delicacy” if not precisely from the pig.

Speaking of war, it is to the Lombards, after the migration to the south between the 2nd and 6th century CE, that we owe the so-called “Civilization of the Pig” and the spread of the culture of pork butchery. As Marcus Terentius Varro testifies in an appendix dedicated to the Gaul population in his ‘De re rustica’ (1st century BCE), it is to them that we must attribute a greater experience in the field of the processing of the pig and its meat. In fact, it was the task of the pater familias (the male head of a household) to take care of portioning the pork sides and salting the parts, establishing a real model of attitude.

During the Lombard reign, there was an enormous increase in livestock farming in the lands that now correspond to Liguria, Piedmont, Veneto, Lombardy and a portion of Emilia Romagna, and the consequent consumption of cured and dried meats. So much so as to establish a real delimitation border, still evident today, between Emilia and Romagna. Even today, the division involves not only the geographical aspect but also the one concerning the filling of fresh pasta, with a tradition based on the use of pork in Emilia, whereas in Romagna sheep’s cheese and, sometimes, seasonal herbs are preferred.

It is in the Lombard period, therefore, between the sixth and eighth century CE, that the actual art of pork butchery was materialized in the first shoulders, pancetta, salami and sausages derived from pork, becoming one of the most important and fruitful food resources. The link between pig and man reaches the early Middle Ages where the preparation techniques of Coppa, salami and pancetta were refined, thanks to the particular favorable conditions for breeding. Evidence of this prolific liaison can be found in an important document present in the inventory of the Brescia Monastery of Santa Giulia, dating back to the beginning of the 10th century, which attests to the predominance of pig farming, about 45% of the animal capital, compared to poultry, in the estates of the Lombard lands. Not only that. In the city of Florence, in the fourteenth century, there were four thousand oxen and calves, eighty thousand sheep and thirty thousand pigs that came from the woods and indigenous breeding. The dense woodlands and temperate climate, therefore, proved excellent for the growth of the pig in the wild, which allowed the development of noble fat.

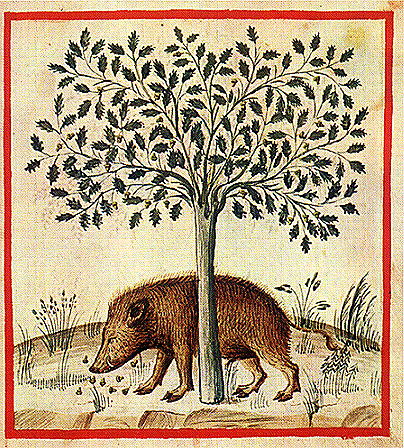

Many other examples of the historical pig breeding and processing are found in the Parma area where, inside the Bobbio Abbey, in Val Trebbia, the practice of pig slaughtering is depicted in a 12th century mosaic. A similar representation is also present in the crypt of the Basilica of San Savino in Piacenza.

In Piacenza itself, we have traces of the practice of pork butchery also in the text by Giulio Landi who in his ‘Formaggiata di sere stentato’, published in 1542, recounts how cured meats and the processing of indigenous pig were equally important and widespread in other Italian towns besides Norcia. The art of pork butchery, because it is an art, handed down from generation to generation is also mentioned in the agronomy treatise ‘Le vinti giornate d’agricoltura et de piaceri de la villa’ (The twenty days of agriculture and the pleasures of the country estate), of 1569 by Agostino Gallo, who maintains that “one should keep pigs to slaughter them fat at the time of cold weather for the needs of the family and of the workers”.

The relation between pig and man is not discussed and analyzed only in the literary field. In cathedrals from Sicily to northern Europe, in fact, the pig plays an important role in the scheduling of peasant’s traditions. In various pictorial representations, the months of November and December were dedicated to the slaughtering and processing of the pig. A sort of didactic calendar as also mentioned by Bonvesin de la Riva in his ‘Tractato dei mesi’ (The months’ treaty) and equally by Folgòre da San Gemignano in ‘Sonetti’ (Sonnets) where he explains how the importance of bringing together the aforementioned operations was attributed to the month of December. Moreover, the pig was given a real diplomatic function as well. The Cardinal of Piacenza, Giulio Alberoni, managed to obtain the benevolence of the Duke of Vendôme exactly thanks to the intrinsic seductive capacity of cured meats, such as salami, of which we have traces in the correspondence between Alberoni himself and Count Ignazio Rocca. On the contrary, the pig and its derivatives could be an occasion for contention and, therefore, for the ‘imbolamento’ – that is, stealing with dexterity – of which Giovanni Boccaccio also speaks in the 8th tale of the sixth day of ‘The Decameron’. Likewise, raiding pigs from enemy lands could be considered part of the spoils of war, as can be seen from the 39th novella of the ‘Trecentonovelle’ (Three hundred novels) by Franco Sacchetti.

Another fundamental point concerning the art of butchery is the use of spices.

Their use in the curing and processing of meats plays a role of social identification in the history of mankind. In fact, the name from the Latin species which means ‘special’, already referred to uncommon, almost extraordinary goods. Extraordinary because they did not belong to everyday use and were not native to the area. They came, instead, from trips to the East and were synonymous with an affluence, a prosperity that only the nobility and the wealthier classes could afford. A symbol of wealth, spices were therefore used in quantity just as further proof and ostentation of the ability to have them. Equally important was the use of salt in the preservation and processing of pork. Salt production was the main activity of the town of Cervia which supplied the so-called ‘white-gold’, branching out throughout northern Italy.

Yet, the processing of meat underwent a real turning point, already in ancient times, from the moment when it was ‘discovered’ that the intestine of the pig itself could be used as the casing and, therefore, of central importance in the procedure following the slaughter of the animal. It is precisely thanks to the assumption that ‘nothing from the pig is thrown away’ and that, therefore, the pig itself contains everything that is needed to obtain the exquisite and valuable cured meats, that the practice of sausage-making began. In the 14th century, in the ‘Libro della Cocina’ (Book of Cuisine) by an anonymous Tuscan author, appeared for the first time the use of this particular technique and, therefore, ‘revolution’ described as “you can fill pork or veal intestine with pork fat and other types of meat, with spices and aromatic herbs”.

Casing, however, was done not only with the pig’s intestine, but also with the rind. We have traces of this practice in 1511 where in Mirandola, still in Emilia Romagna, after the city was besieged and with the prospect of a period of famine, the inhabitants began to prepare what we still call cotechini and, later on, to carry out the stuffing by using the pig’s legs, hence the zampone. Both of these cured meats see the necessary presence and intrinsic capacity for preservation and taste that belongs to the aforementioned spices, to which the Modena almanac of 1866 refers, which identifies them as “pulverized aromas, Ceylon cinnamon, mace, allspice, nutmeg, strong crushed pepper”.

As for the diffusion of mortadella, another traditional cured meat of Emilia Romagna or, better, typical of Bologna, it is due to Ovidio Montalbani, a doctor and philosopher of the 17th century. In a public notice issued by the city of Bologna in 1661, the characteristic production of this cured meat using only pork meat was clearly and strictly respected, under penalty of exemplary punishments and penalties. This was followed by a new notice in 1720, the ’Dichiarazione del Bando delle Mortadelle’. The document declared the attribution of the traditional and original recipe to the exclusive possession of the city’s Guild of the ‘Salaroli’ (artisans specialized in the processing and sale of salted pork meats).

Returning to the history of salami and its origins, we are able to focus on the fundamental stages of the evolution of the art of pork butchery from the text by Alda Tacca, ‘La storia del felino’ (‘The history of Felino’).

The first depictions of this salami date back to the Egyptian era, in 1166 BCE, inside the tomb of Pharaoh Ramesses III in Thebes. Likewise, in Greek and Roman times, traces of the proven presence and appreciation of the salami reside in the etymology of the term ‘luganica’, of which ‘lucanicus’, therefore, coming from the historical region of Lucania. On the frieze slab dedicated to the Aquarius sign of the zodiac, inside the Baptistery of Parma (1196 – 1307), two artifacts stand out which have all the appearance of two salamis and, more precisely, are of a size and shape that can be traced back to Salame Felino, of which we still know the merit. Although there is no doubt on the proven presence of representations of the salami effigy, various possibilities are compared on the provenance and origin of the word itself. The first hypothesis concerns the origin from the term ‘salamme’ that appears for the first time in 1560, as it can be read in the Etymological Dictionary of the Italian Language by Manlio Cortelazzo and Paolo Zolli. This attribution was however anticipated by a text dated 1436 which tells of a soldier employed by the Duke of Milan, who would have requested “porchos viginti a carnibus pro sallamine“, that is, twenty pigs whose meat was suitable for making salami.

Although until the end of the 15th century it was more common to refer to this salami with the term botulus or insicia, the second hypothesis of origin of the term that identifies it is to be found in the link between the salami and what flavors it. In Bologna, already from the 13th century, there were various active guilds. Two stand out for our history of cured meats: the first of the ‘Salaroli’, which officially came together in 1294 when it already counted as many as 281 professionals among its members, and the other of the ‘Lardaroli’ (lard makers), from which the term salamen came from, decreed by ‘Il trinciante” (The carver), the first text devoted exclusively to the artful carving of meats, fish and vegetables, written by Vincenzo Cervio and published in 1581.

However, it is by returning to the text by Alda Tacca that we gather how cured meats were present at court banquets as well. Specifically, the Salame Felino was a constant presence on the tables of the influential Farnese family, the House of Bourbon and Marie Louise I, Duchess of Parma, to the point of having more importance and economic value than prosciutto. Attributed to the same historical period is the collection of playful short-poems with notes by Antonio Frizzi, ‘La Salameide’, published in Venice in 1772, which explains the connection of Salame Felino with the Salama da sugo (a particular pork salami typical of the province of Ferrara, which is consumed after cooking) and the proven adaptability of pork meat served in lavish banquets that “in many forms is transformed, and parted / The meat of the Piglet in the pork slaughter / That makes the magical art amazed.”

The proximity in which it was customary to eat cured meats was not limited by territorial contiguity. The function of salt was, in fact, to allow cured meats to be transported and preserved. As can be seen from the documents found at the State Archives in Genoa, there are testimonies of how the products obtained from pork processing were enjoyed even far from the production areas. From the same documents, it emerges that between the 1700s and 1800s Genoese privateers stowed the ships with cured meats such as prosciuttos from Emilia and Veneto. These regions, heralds of the first models of food laboratories and cured meats production factories, could therefore afford to export their products even outside the Bel Paese, thanks also to two testimonials ante litteram, Gioachino Rossini and Niccolò Paganini. Yet, it is with the industrial revolution that salami becomes increasingly popular.

In fact, thanks to the industrialized transformation of raw materials, even pork butchery witnessed its maximum development, culminating in the 1980s and the consequent post-war economic boom. It was in response to the industrialization itself that, at the end of the century, a real reversal of intents occurred, promoting a return to the craftsmanship of the art of butchery and to a more conscious and reduced consumption. A trend that is still current, after all, at all levels of nutrition.